What once was a coal city is now a center for culture and creativity.

Pittsburgh’s transformation from a steel city to an artistic hub is evident in neighborhoods like the Hill District and Lawrenceville, where public art and street murals decorate the urban fabric. But a new exhibit in the Frick Fine Arts Building is calling attention to the lack of black artists in popular visual arts culture.

“Exposure: Black Voices in the Arts,” which opened Nov. 9, and will run through Dec. 11, in the Frick Fine Arts Building’s University Gallery, is an initiative by Janet McCall, history of art and architecture professor, and her museum studies seminar. It aims to expose “the dearth of Black artists and curators represented in institutions and galleries,” according to the Nov. 16, press release.

“[Exposure] is about exposing not only the lack of representation of black artists in the art scene,” said Alexis Henry, a senior double majoring in history and history of art and architecture and a student in the museum studies seminar that organized the exhibit, “but also the wealth of black artists that are creating in Pittsburgh.”

Janet McCall, who teaches the museum studies seminar, said the exhibit will have an impact on Pitt community as well as that of the city by drawing awareness to the work as a tool for development and career building for students.

“Black Voices” features 54 artists, some of whom are Pitt students. The rest are working Pittsburgh artists, like cartoonist Marcel Walker. Walker submitted two works — a self-portrait and an issue of his comic book “Hero Corp., International.”

“I am very happy that my work fits in so well with the themes of the exhibition and the other artists’ work, yet still stands alone in terms of style and what it is,” Walker said. “That’s what most artists set out to achieve.”

“Hero Corp’s” Facebook describes the series as a group of superheroes dedicated to “the welfare of others, regardless of the dangers associated with this duty … The betterment and safeguarding of humanity is our ultimate goal. We are bound in loyalty to our fellow agents and we accept these responsibilities as an honor.”

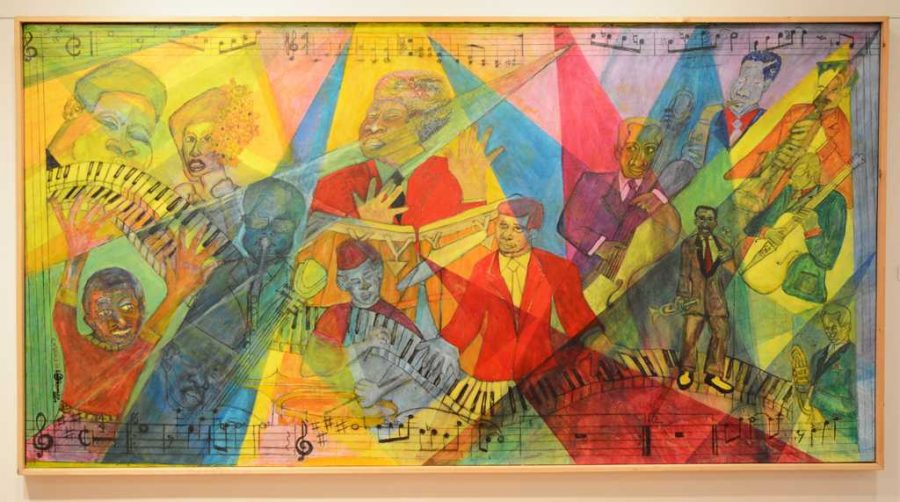

The exhibit’s mediums feature a range of paintings, sculptures, photographs and textiles. The sculptures sprinkle the gallery’s five rooms, each boasting a different sub-theme within African-American artist culture.

One room houses a photograph series documenting UPMC Braddock’s — which closed Jan. 31, 2010 — controversial destruction in which different children of color are shown playing in the hospital’s rubble.

Others capture children staring into the lens, their expressions mostly defeated or stoic, highlighting the detrimental effects the hospital’s closing had on the community.

Another room harbors paintings and sculptures of different jazz instruments, recalling the lighter subject of jazz and soul music rooted within the African-American community.

The museum studies class distributed a release asking for submissions from various artists all around the Pittsburgh area in October. When Natiq Jalil heard of the exhibit, he submitted his painting, “Street Telemetry.”

Jalil’s work is noticeably only partially colored. The face of the black male — the center of the painting — is colored brown with hints of reds and blues. While the hands are also partially colored, the vast majority of the clothing and outer perimeter of the painting is white.

“I was thinking about the way so many black men must switch roles at the drop of a dime,” Jalil said. “We must be street savvy to survive the neighborhood, then clean cut and nondescript in order to fit in with the corporate world, etc.

The skill with which some of us do this is astonishing.”

The only consistency Jalil is getting at here is the face of the man. Regardless of what role the man is playing, his face stays the same. That’s why it’s colored — it’s permanent. Everything around him can freely change, which gives the ability to mold what’s around them to fit into a certain role.

“I saw submitting my work as an opportunity to show that being black is multidimensional,” said painter Pascale Joseph, who submitted an abstract painting titled “Une Autre Nom Pour la Niege.” “The culture, the voices, the talent — all of these things are rich and thriving with a diversity that people tend to overlook or forget.”

“Black Voices” is a wake-up call meant to shake the underrepresentation of black artists in art institutions like galleries and museums.

“I’d love to see the day when shows like this are no longer an anomaly,” Walker said. “That might happen.”