At “Prescribed to Death,” an opioid memorial in the William Pitt Union, a steady flow of people moved through the room in a respectful silence. People saw a large, black wall dotted with small white pills, and a screen with a number in the thousands growing higher by the second.

The memorial made it clear that both patients and physicians are responsible for starting, and now ending, the opioid epidemic. Everyone involved in the epidemic shoulders part of the blame, and it’s now both parties’ duty to keep the numbers on the screen from growing.

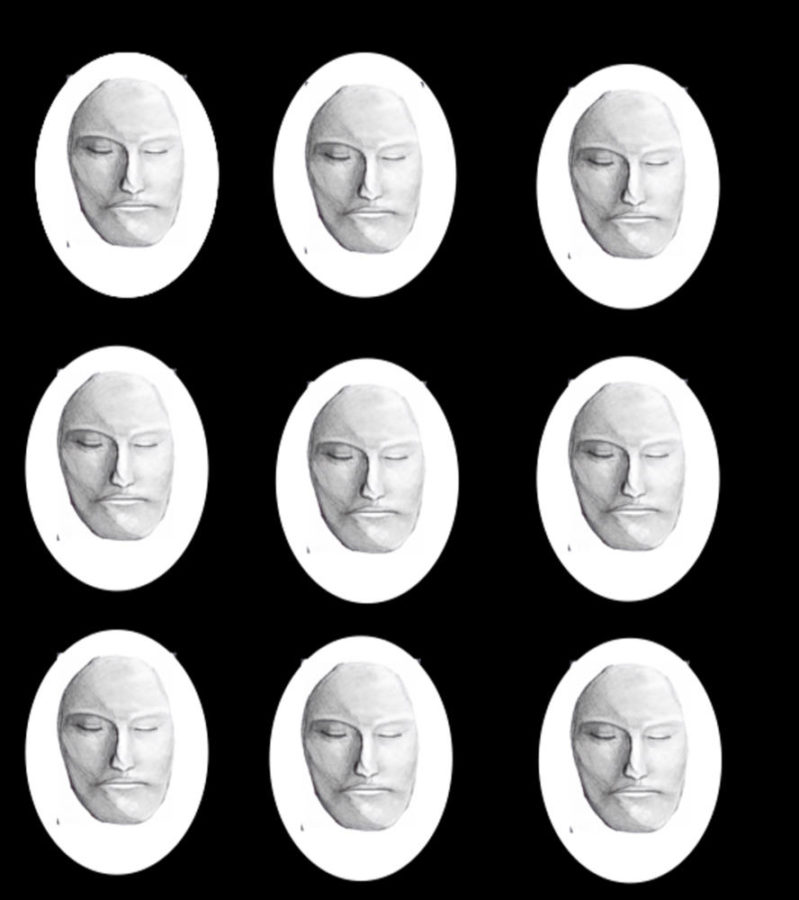

Further inside, more aspects of the memorial came into focus — the number on the screen represented each person who had died from opioid abuse, and each small white dot on the wall bore an engraving of the face of someone ravaged by opioid addiction, a permanent rendering of a personal memory.

Visitors to the memorial received a “warn me” label to apply to their insurance cards, alerting physicians to tell them if they prescribe them opioids and inform the of what non-addictive alternatives are available. According to a National Safety Council poll, 99 percent of physicians prescribe opioids for a longer period of time than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends — and most of them aren’t even aware of alternate options for treating acute pain.

Looking more closely at the main feature of the memorial, wall displaying 22,000 white pills, it was easy to distinguish the faces on each pill. One showed the smooth, feminine features of a young woman. Another sketched the receding hairline of an older man.

This wall is a stark reminder that real people become victims of an awful disease, immortalizing the faces of those behind the number — 22,000, the estimated number of people who died in the opioid crisis last year. On a TV screen attached nearby, visitors could watch a demonstration of the machine as it carves a new face every 24 minutes — symbolizing how often Americans die from opioid overdose.

Yet doctors continue to prescribe medication that has consistently proven to be both highly addictive and a gateway to lethal drugs like heroin. Not only that, but it’s problematic for patients to be unaware of the addictive and lethal effects of their medications.

Legislators in Maine proposed a bill last year requiring doctors to inform patients of opioids’ addictiveness when they are prescribed, and here in Pittsburgh, nurse practitioner Melissa Jones devotes her days to informing doctors of opioid prescriptions’ riskiness.

“It was in doctors’ offices where the epidemic began,” The Associated Press wrote in an article about Jones’ work, “and it’s in doctors’ offices where it must be fought.”

It’s this kind of action that will begin to make real change in the opioid crisis.

The medical advisor of the National Safety Council, the nonprofit public service organization which created the memorial, recognized the tragic consequences of opioid use.

“Opioids do not kill pain. They kill people,” Dr. Donald Teater, NSC’s medical advisor, said. “Doctors are well-intentioned … [but] we need more education and training if we want to treat pain most effectively.”

Doctors and public health experts should encourage patients to educate themselves on whether certain pain medications are highly addictive. This knowledge will then empower people to advocate for pain management plans that don’t require opioids.

Continuing through the memorial, sobering messages were written across the walls reminding visitors how easy it is to become addicted to opioids. Prescription bottles sat inside glass medical cabinets attached to the memorial’s walls.

“Unfortunately, 33% of painkiller users don’t know they’re taking opioids,” one cabinet read. Another says they aren’t any more effective than over-the-counter medications for acute pain relief.

This was all news to me — and as I continued to walk through the memorial, I realized how ignorant I was regarding the whole situation.

It is clear that more conversations, such as the one the memorial has successfully started on campus, must occur across the country. I’m sure I’m not the only one who walked into the memorial uninformed about the reality of the opioid epidemic — being unaware of the facts will only perpetuate the criminalization and misunderstanding of addicts.

Perhaps one of the most alarming elements of the opioid epidemic is that you can become addicted to opioids after simply seeking treatment for knee pain. Your physician, the one who is supposed to heal you, ends up implicit in the beginning of your addiction.

Of course, most physicians aren’t out to sabotage their patients. But more medical schools need to address proper pain management and addiction prevention. In fact, the White House asked medical schools to pledge to expand their educational programs on opioid prescription according to CDC guidelines back in 2016.

For physicians already in the field, Dr. Theodore Parran has been teaching a remedial course for those who have been identified as overprescribers by licensing boards. While these are good first steps, the rest of the country must follow suit.

Patients need to understand how opioids affect the body as well as the risk of addiction in order to alert their physicians if they fear they’re becoming addicted. There are resources available for them to do so, like the CDC opioid fact sheet for patients which informs them of the risk and side effects of opioid use, as well as what one should do if they are prescribed opioids.

This, in turn, will help nurture a healthier and more trusting patient-physician relationship — rendering education as a driving force for change.