“Emma” is a joyous, low-stakes escape into the past

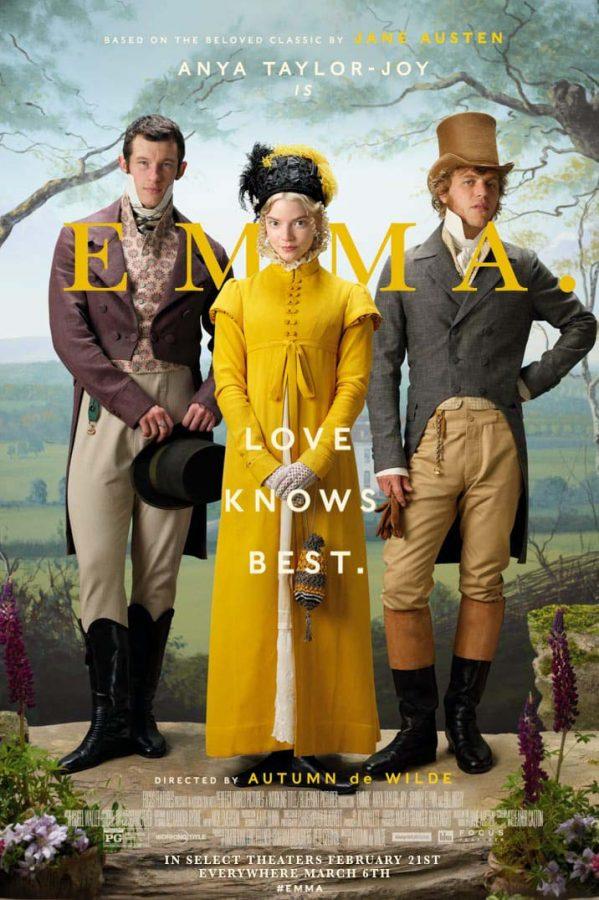

“Emma” poster via Perfect World Pictures, Working Title Films, and Blueprint Pictures.

“Emma” is a film adaptation of a Jane Austen novel of the same name.

February 27, 2020

Adapting for the screen a novel that’s a solid few years into its third century of existence is far from an easy task. For Jane Austen’s “Emma,” there have been seven miniseries adaptations and two film versions from the mid 1990s, a straightforward telling starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Amy Heckerling’s classic teen-drama twist on the story, “Clueless.”

Director Autumn de Wilde and writer Eleanor Catton face the challenge of bringing something new to Austen’s text while faithfully shifting it to the screen. They don’t twist the book around as some other literary adaptations have, instead having their “Emma” stick to its strong points –– a slate full of great performances, a witty script, top-tier design and cinematography –– to give you a wildly entertaining two hours of fancy dress and snippy Brits.

“Emma” is de Wilde’s feature film directorial debut, but she holds a remarkable oeuvre of photography and music video direction, having worked with Elliott Smith, The White Stripes, Death Cab for Cutie and most other notable indie rock figures of the past few decades. The skill transference is evident, with shots clearly composed by the confident hand of a stellar photographer. Nearly every frame could stand alone as a gorgeous still photo, blocked and lit to perfection.

More surprisingly, her direction in other areas is almost as assured, pulling pitch-perfect performances out of a cast that’s well-rounded, if not star-studded. Mostly made up of actors known for TV work or minor parts in blockbusters, the ensemble elevates together to feature film. One of these actors delivers the film’s funniest performance, with Tanya Reynolds, best known as Lily on Netflix’s “Sex Education,” taking a big bite out of the scenery as the high-falutin Mrs. Elton. Bill Nighy, one of the most dependable actors alive –– we’ll not hold “Detective Pikachu” against him –– is the only “big name” in the cast and is delightful as Emma’s elderly father, who’s just about had it with everything.

Emma herself is played by Anya Taylor-Joy, who has enjoyed a few years as an indie darling on the back of Robert Eggers’ “The Witch” and starring in a pair of M. Night Shyamalan successes. She now seems ready for a push to the A-list with “Emma.” She plays the “handsome, clever and rich” heroine of the novel’s opening line with an unbridled charm, pulling Austen’s wicked-sharp sense of humor to the forefront of her portrayal. She spends the film hopping between exasperating others and being exasperated herself, playing off of Nighy, the relentlessly annoying Miss Bates (Miranda Hart), hopeless Mr. Elton (Josh O’Connor) and the rest of the cast, who admirably rise to, and stay at, Taylor-Joy’s level.

Taylor-Joy’s primary supporters are Emma’s best friend, Harriet Smith (Mia Goth,) and –– semi-spoilers, if you live in 1815 –– her romantic interest, the gallant Mr. Knightley (Johnny Flynn). Goth, who, like Taylor-Joy, broke out with doom and gloom roles in indie horror flicks, plays far afield from her previously established type, embodying Harriet with a pure glee in her lighter moments and a timid sadness in her trying times. Harriet’s relationship with Emma, a real friendship that survives the latter’s misguided romantic machinations at the former’s expense, is brought alive by the two actresses, pulling it into the future without even having to change the setting, à la “Clueless.”

“Emma” moves at a healthy clip from one of the titular character’s problems to another, rarely settling in for anything resembling a serene, picturesque portrait of English pastorality. This refusal to settle comfortably into the idyll sets up a perfect dropping of the other shoe about three-quarters of the way through the film, when Emma steps too far over the line of tactlessness and nearly traumatizes a friend. Taylor-Joy lets the facade drop in the aftermath, letting the tears fall as her voice rises and breaks. It’s a standout moment in an adaptation that leans almost entirely into the farce of Austen’s text during the rest of its runtime — a draft of cool air that lends the resolution a real beauty.

Elsewhere, de Wilde and Catton shy away from leaving the comfortable realm of snappy dialogue and screwball comedy driven by awkward silences, perhaps over-lightening the load the film could conceivably have borne. “Emma” manages to succeed, most of the time, by holding back from the line of pure saccharinity, maintaining its air of intentional sweetness without overstaying its welcome. It treads it very carefully, threading every moment with the possibility of a tension-deflating pratfall, but it pulls through, leveraging its own lightness into a floating sense of satisfaction.

The aristocratic silliness of Austen’s novel is brilliantly rendered in a whimsical set of production values — with costumes that may as well already have designer Alexandra Byrne writing her acceptance speech for next year’s Oscars, a striking score from David Schweitzer and “Fleabag” composer Isobel Waller-Bridge and director of photography Christopher Blauvelt’s stunning cinematography.

De Wilde and Blauvelt frame their comedy of manners with two-shots and close-ups aplenty to offset the prettier wide shots of impeccably decorated interiors. Taylor-Joy is often framed either alone looking straight into the camera and then away again as Emma thinks through her social maneuvers or alongside Nighy, as comfortable as he is clearly not floating amongst the airs of high society.

De Wilde’s “Emma” is a great deal of fun, both an impossibly earnest bit of light storytelling and a skewering satire of a high society that doesn’t really exist anymore –– but that’s where the fun lies. It’s brilliantly low-stakes and detached from the many troubles of the present — a clean breeze through 2019’s cinematic smog of birthday party homicides and world wars, evil clowns and scarlet fevers. “Emma” kicks off 2020 in indie-adjacent cinema with a story that’s just a story, a tale to watch and laugh at and, ultimately, love.