Ibrahima Seck said studying the history of slavery works to deconstruct racism in America and around the globe.

“We have to deconstruct racism if we want to solve the problem of this country, but also the problem of the world,” Seck said.

Seck, a member of the University of Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar in Senegal and director of research at the Whitney Plantation Slavery Museum in Wallace, Louisiana, gave the opening lecture of Pitt’s history department’s speaker series on slavery and memorialization in the Atlantic world. The event was cosponsored by the Center for African Studies, the Center for Latin American Studies and the Early Modern Worlds initiative.

According to the event description, the Whitney Plantation Slavery Museum is a former indigo and then sugar plantation, now converted into a museum focusing on slavery. The museum focuses on the perspectives of Louisiana’s enslaved people using restored historic buildings, museum exhibits, memorial artwork and hundreds of first-person narratives from enslaved individuals.

Seck began the lecture by explaining the founding of the plantation by the Haydels — a German immigrant family. He said the French Company of the West Indies recruited over 7,000 German immigrants to colonize Louisiana.

“There was a time when the French Company was having a hard time finding colonies because the news from the Mississippi River was so bad,” Seck said. “Many people died of disease. Many people died fighting against the Native Americans who were different in their lands, and also many people died of starvation.”

Seck said the solution to these problems came from Africa. The people sent to buy slaves in West Africa to bring back to Louisiana specifically sought people who knew how to cultivate rice, according to Seck.

“The first ship arrived in 1719, and in 1721 Louisiana had enough rice to feed its population,” Seck said. “So slavery is not just about taking people who have the reputation to be strong and who are able to work long hours under the hot sun. It’s also about skills. They took over the rice growers who saved the colony from starvation.”

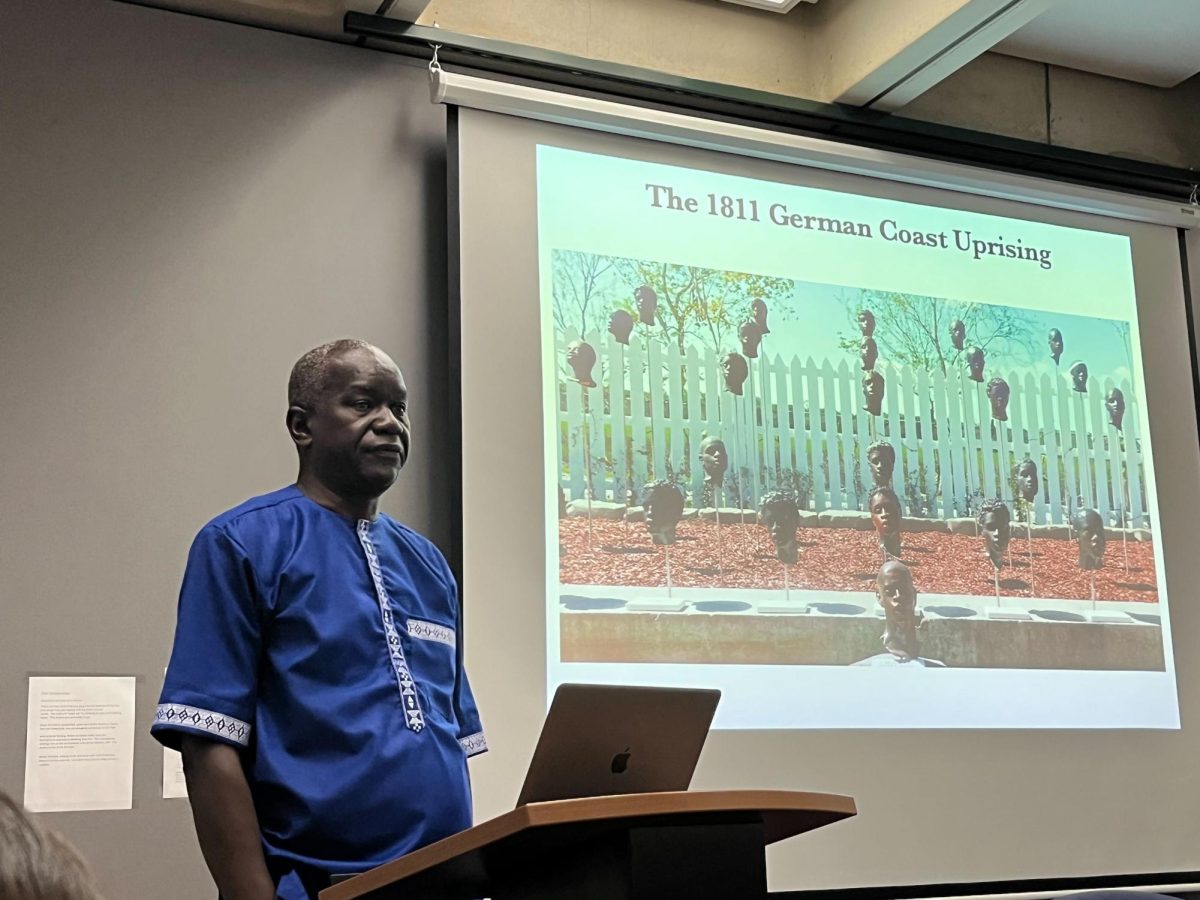

Seck also showed photos of the 1811 German Coast, Louisiana, slave uprising memorial sculpture at the museum that features 63 ceramic heads depicting the heads of enslaved people that were murdered after starting an uprising, mounted on beams stuck out of the ground. Seck said this was the latest memorial built and that its installment caused some controversy within the museum organization.

“Some people just wish to destroy the place, water down the narratives,” Seck said. “Some people say it is graphic. I’m gonna tell you what is graphic.”

Seck then described the uprising and explained how the enslaved people of Louisiana “decided to do like the Haitians — destroy slavery and build a free nation.” He said they fought from Jan. 8 to Jan. 13, but added that they did not have the numbers or firepower they needed.

“They were finally defeated. Many were killed in action, many went missing,” Seck said. “And those who were captured were taken to different tribunals in St. John the Baptist Parish, St. Charles Parish.”

Pernille Røge, associate professor at Pitt’s department of history, co-organized the speaker series with her fellow history professors Keila Grinberg and Alaina Roberts. Røge said she and her colleagues organized the event because they feel that the history of slavery is currently at the forefront of public consciousness and debate.

“As the last few years have shown, this attention has manifested itself in several ways in the United States,” Røge said. “Efforts to rewrite or reframe the national historical narrative to better account for the role of slavery and colonization has garnered fruit in initiatives such as the New York Times 1619 project, and some have welcomed these efforts as we’ve seen, but others have also strongly rejected them.”

Røge said the United States is at war with itself over how the history of slavery should be taught in schools.

“Indeed, 18 states have signed into law or embraced state level bills that restrict the teaching of what has been called critical race theory, or otherwise limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism in the classroom,” Røge said.

After the lecture, Seck took a couple of questions from the audience. Jerome Branche, a professor of Latin American literature and cultural studies at Pitt, asked about the difference between this plantation museum and other plantations that are open to the public.

Seck responded by saying the Whitney plantation is different in that it doesn’t focus on the “big house” and the “masters” like other plantations do.

“People who visit the Whitney plantation and then go to Oak Alley or any of the other plantations, and they don’t hear anything about Africans and their descendants,” Seck said. “They ask them questions and they cannot answer. And that’s why many of these places, they hire very good historians to do the job — to introduce slavery into the curriculum.