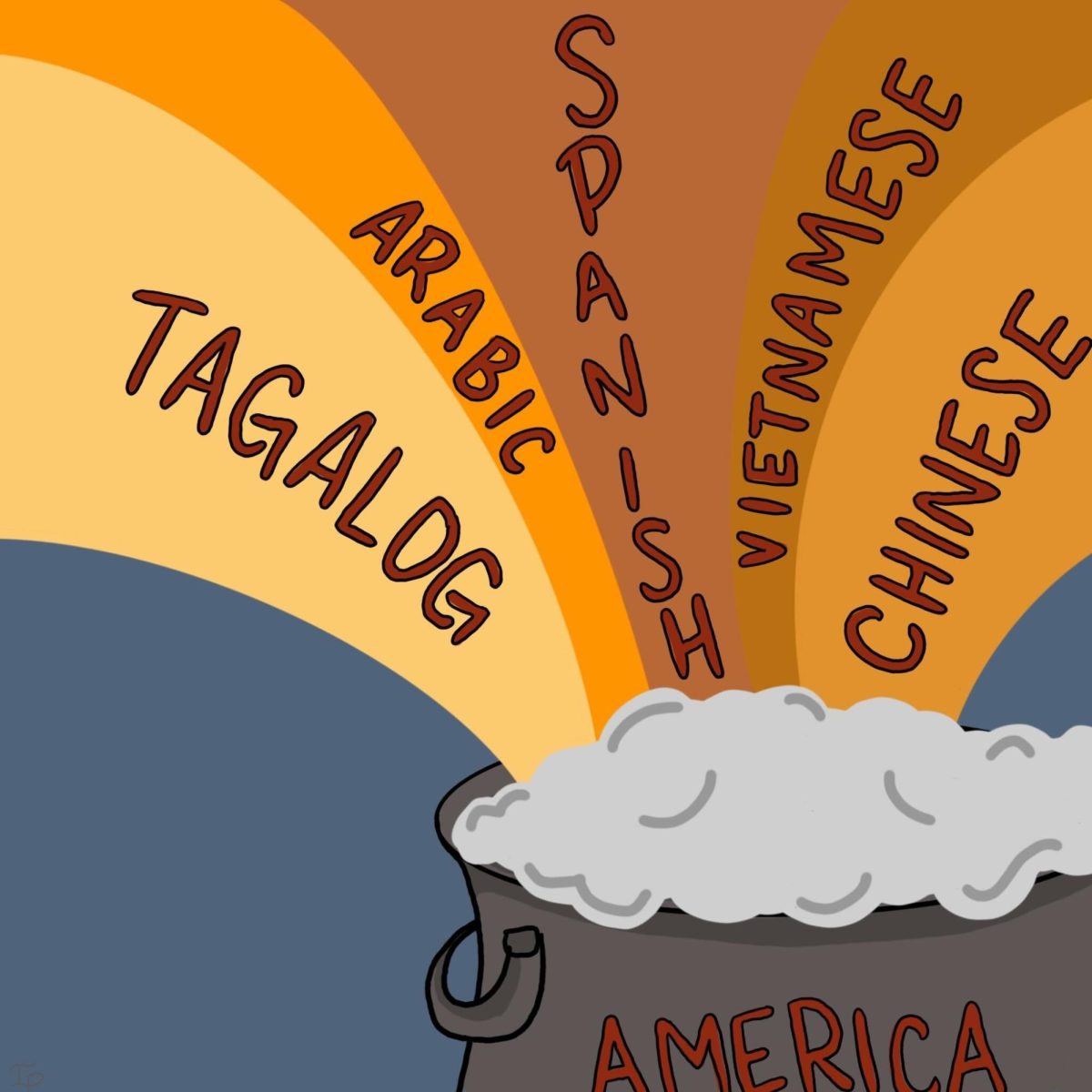

There are somewhere between 350 to 430 languages spoken across the United States. Romantic languages. Afro-Asiatic languages. Hellenic languages.

Roughly 30 major dialects exist under the umbrella of English, with dozens of subclasses and amalgamations beneath greater identities. African American Vernacular English. Southern English. Cajun English.

On March 1, President Donald Trump signed an executive order declaring English as the official language of the United States. And while some may be surprised it wasn’t beforehand, there is a reason there was no official language for 248 years. The founding fathers did not see it necessary to designate an official language. They recognized that English was the de facto standard, but the new government thought making a language official to an American identity would ostracize the French, Dutch, German and other non-English speaking citizens in the newfound republic. It’s the same reason there is no official religion or church of the United States.

There is no such thing as “standard English.” We may all have the same definition of “house,” but I drop the objects or subjects from the ends of my sentences — Chicago suburbs. Someone else uses double negatives or omits “is” and “are” — AAVE. People across the country pronounce their vowels differently from one another — Boston versus California.

Standardizing language or privileging one dialect or language over the other creates a moral hierarchy that is best left in the past. If my Midwestern English and Chicago vowels are standard, then the Philly accent becomes wrong. Southern dialects and twang become incorrect. The Spanish spoken in Texas becomes erroneous.

The United States is a multicultural nation rich in a variety of ethnicities, languages and lifestyles. To make one identity the standard is to erase the linguistic and cultural diversity that has defined America since its inception.

Trump’s executive order is devastating on multiple fronts. Firstly, dignifying English as the official language completely ostracizes those who do not regularly speak the language or those who do not speak English at all — a population that makes up 21.6% of the country. Secondly, the executive order reeks of white supremacy, sending a clear message that if you are not white and do not speak English, then you are less than and not a real American. I don’t put any of this past the current president. I am not surprised, but I am deeply disappointed.

A common feeling these days.

And while Trump officially declared the United States a nation that values the voices of English speakers — white folk — over the voices of non-English speakers, he forgets the universal truth that people are going to speak. They are going to speak behind closed doors and behind each other’s backs. They are going to preserve their languages and cultures, passing them down and refusing to let a government erase their words. The American government and other imperial regimes have tried, and occasionally succeeded, but have more often failed.

Protesting Trump and the pervasive grip of white supremacy is now as simple as speaking another language. Trump and the Republican Party made it easy to push back, easy to defy them in the most fundamental way possible — by refusing to let English be the sole marker of American identity.

Inciting change doesn’t have to be directly aimed toward the man in charge, spitting on his face in an act of protest. It can begin below the eyes of the government, in the spaces they are not looking and don’t understand. It begins in teaching Spanish in schools, in Black children learning AAVE from their parents, in families holding on to their mother tongues despite the pressure to assimilate. It begins in pride, in ownership of the voices that cannot be silenced.

In his book “Domination and the Arts of Resistance,” James Scott wrote, “Part of the relative immunity of the spoken word from surveillance springs from its low technological level. Printing presses and copying machines may be seized, radio transmitters may be located, even typewriters and tape recorders may be taken, but short of killing its bearer, the human voice is irrepressible.”

People are going to talk. People are going to sing. People are going to create art and shove their identity into their environments and take up space. If we don’t, we give in to the erasure that Trump’s executive order demands.

You cannot legislate or control language without consequence. The racist and xenophobic undertones of such a decree do not go without resistance. Moral connotations, “right” or “wrong” language, mean nothing to people who value diversity and who are open to experiencing a heterogeneous country. It means nothing to people who refuse to be silenced, who choose to resist not with weapons or protests in the streets, but with their words, their dialects and their accents.

Language is power, and it cannot easily be suppressed if we do not let it. Every conversation in another tongue, every refusal to anglicize a name, every instance of a child learning their grandparents’ language is an act of defiance.

The government may attempt to dictate the language of our nation, but the people will always decide the language of their lives.

Livia LaMarca is the assistant editor of the opinions desk who misses using the Oxford comma. She mostly writes about American political discourse, US pop culture and social movements. Write to her at lll60@pitt.edu to share your own opinions!