Are homecoming candidates the faces of our University?

October 24, 2014

Homecoming court traditionally selected students who represent a wide assortment of their university’s student body — or, at least, they did a few decades ago.

Originally, homecoming candidates were meant to portray to the alumni what the university and its students were up to.

Today though, the original tradition of using the King and Queen as figureheads for a university is dead.

While a court may have noteworthy members who do good deeds, they are typically involved in the same types of activities year after year.

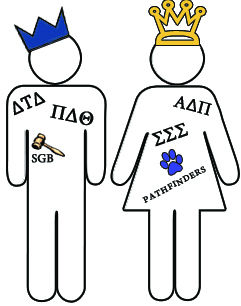

Students who make up a homecoming court almost inevitably fit the prototype of a very involved student — Greek life and Student Government members, Pathfinders or members of some other popular campus organization often make up the ballot. But where are the students from Habitat for Humanity? Or the ones who have aided in fruitful scientific research? Why not select a student who represents a smaller demographic?

In researching past Kings and Queens at Pitt, the answer became clear: large organizations dominate the running — financially and socially.

First and foremost, there is no effort to ensure that candidates fully represent what Pitt has to offer.

Mary Jean Lovett, adviser to the Blue and Gold Society, said determining what organizations past candidates were involved in was “asking the near impossible!!!”

The Blue and Gold Society does not ask candidates to list the activities they are involved in, Lovett said, and could only provide the names of the Kings and Queens from the past three years.

The University does not keep clear records of past courts. Could it be because they don’t need to? Candidates typically come from large, highly funded organizations, so why should the University care to keep track?

The supposed expectation that the Homecoming court is supposed to reflect of the student body — especially the King and Queen — is, therefore, non-existent. In the last three homecoming courts at Pitt, the large organization stereotype has repeated itself. In 2011, Andrew Kaylor, a brother of Delta Tau Delta, was voted King. Jules Bursic, 2012’s Homecoming Queen, was a member of the dance team. Last year, a member of Student Government Board and the Alpha Delta Pi sorority, Amelia Brause, was voted Queen.

Longstanding trends solidify this more recent pattern. Between 2004 and 2006, all Homecoming Kings and Queens at Pitt were involved in Greek life. Mia Dragoslovich, Queen in 2007, was the first to break this cycle. She was a Pitt Pathfinder and a resident assistant in the Litchfield Towers. But the court has diverted back into the Greek life trend in recent years.

Even if students are not from Greek life, they are often involved in huge organizations, like band, club sports or Pathfinders. This unwritten qualification inhibits independent students or those from smaller clubs to succeed in becoming King or Queen.

What do these student groups have in common? Funding. Fraternities and sororities, specifically, bring in money for the University. In 2011, Kaylor’s fraternity donated $1,000 to the Pitt Dance Marathon — and this is just one small example of the capability of Greek spending. Other large organizations, such as popular club sports teams, help contribute to the branding of the Panthers athletics — not exactly a fiscally simplistic effort.

Nick Bunner, a 2011 Pitt Homecoming King candidate, said running for the crown was expensive.

“I spent close to $1,000 campaigning for homecoming. T-shirts were $400 to $500, $200 on banners … probably like another $100 to $200 on candy and food,” he said.

He said in his fraternity, Phi Delta Theta, “it was expected to have a senior run.” So they heavily supported his campaign, both fiscally and organizationally.

Valerie Gatto, a 2011 Homecoming Queen candidate from Sigma Sigma Sigma sorority, said she spent roughly $3,000 on sponsorship. She used T-shirts, towels donning her slogan, “Gotta go Gatto!” that mimicked the Terrible Towel, and went to every business she could for support, which came in funding and food.

“Quaker Steak & Lube gave me unlimited wings — handed them out to everybody,” she said.

Of course, Gatto’s sorority sisters helped alleviate her financial burden as much as they could as well.

“They were really supportive … There’s two whole weeks of campaigning … everybody was excited to help me,” Gatto said of her sorority sisters.

Without the help of a large organization, it’s difficult to fund a campaign for Homecoming. But does the money go to anything other than a candidate’s campaign?

While the Alumni Association requires all candidates to support a charity, “there’s no accountability for ever giving anything,” according to Bunner. He recalled three Homecoming Queen candidates who “supported” Make-A-Wish during the year he ran. According to Bunner, they tried to make the case that someone involved in the foundation might “wish to meet a homecoming Queen.”

The lack of diversity in clubs and activities comes down to nickels and dimes. Merit doesn’t seem to matter, and obscure clubs don’t stand a chance.

Because candidates and voters alike feel that they cannot break the cycle of Homecoming trends, Pitt has traditionally experienced apathy among voters. In The Pitt News’ 2002 Homecoming Edition, Homecoming King candidate Bob Chatlak said, “Honestly, the majority of people here don’t vote.”

Those running for court show the same disillusionment. In The Pitt News’ 2003 Homecoming Edition, Brian Palmer, who was voted King that year said, “It’s a popularity contest … That’s the way it has always been done.” A 2002 candidate for Queen, Cherise Curdie, told The Pitt News that her sorority house voted for her to run. “So I just did,” she said.

Perhaps if the Blue and Gold Society filtered Homecoming applicants more effectively, we could break the cycle of superficiality.

Future applications could feature a section in which students must describe their extracurricular activities. They should include what they have accomplished for their charity of choice and shift the focus from popularity to philanthropy.

If Pitt and the Blue and Gold had more stringent requirements — more than a 2.5 GPA, good judicial standing and at least one “primary” sponsor — the University can become more selective and promote meritocracy and diversity in terms of what organizations candidates come from. To further level the playing field, Blue and Gold could also place a cap on the amount of money candidates are allowed to spend on their campaigns.

If Homecoming court is diversified in these ways, it could give more meaning to what has become a trivial, superficial practice. Students who care about bringing positive attention to their University through their influence could rise above those who do it for popularity. In this way, they could help illuminate smaller organizations and the great work that they do.

“Honestly, one of my big things is recognition for some of the more smaller groups on campus…,” said 2014 candidate Sara Gdowik, who is sponsored by the honors frat Pi Sigma Pi, the service sorority Gamma Sigma Sigma and club soccer.

Blue and Gold must put more of an emphasis on the smaller clubs themselves. After all, it’s not the past candidates’ fault — they had the means to run, why shouldn’t they have? But students from other organizations simply do not have the means.

To those who oppose these reforms because Homecoming practices are “tradition,” we say: not all traditions should be kept.