“What … are you?”

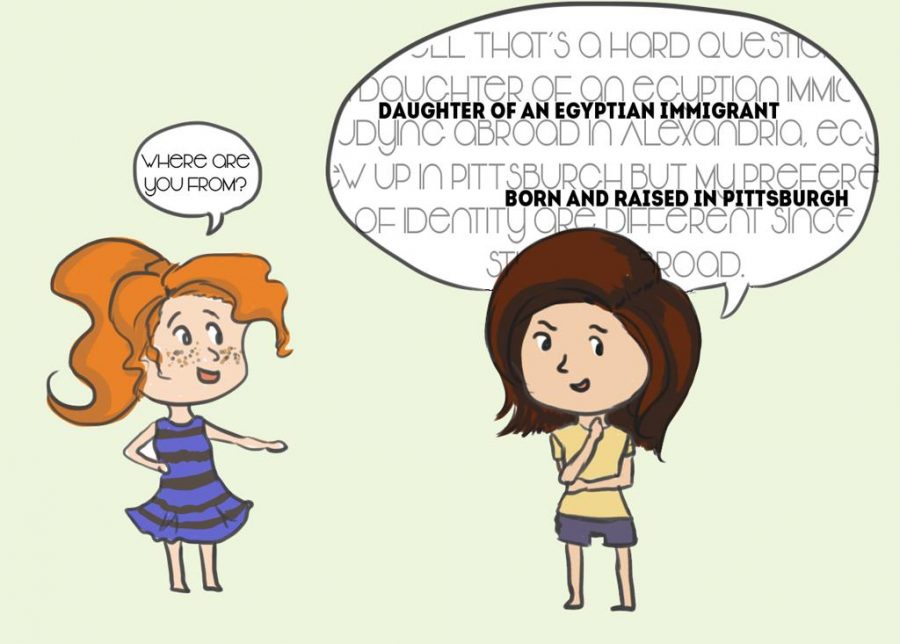

Since I look so ethnically ambiguous — or for a lack of small talk — people often ask me where I’m from.

I’m not sure whether my identity is tied to a single place, so I’ve always struggled to answer the question. I’d rather they ask me the meaning of life.

“Well, my dad is Egyptian and my mom is Chinese — but she was born and raised in the Philippines — and I was born in Nebraska, but I grew up here in Pittsburgh.”

Did you catch that? Or should I say it again?

This summer, I seized the opportunity to study abroad in Alexandria, Egypt. Once there, I obsessed over the question of where I consider myself to be “from,” and what makes a place “home.” I discovered that, on the surface, it seems easy to say what home is — where we live, where we were born, where we grew up — but in reality, one’s home is based on a conglomeration of concrete and qualitative emotional factors.

As I hugged my family goodbye and finally turned toward the Pittsburgh International Airport, I felt an instant sense of loss. I was leaving behind the culture I grew up in, my family, my close friends and my mother language. And for once, the concept of home seemed simple.

When I arrived in Egypt, the frequency of my least favorite question at least doubled, if not tripled.

Egyptians are curious people. Almost every time my accent betrayed my non-native status, I got a wide-eyed look and a “Where are you from?” Here, answering was easy.

“I’m from America.” That was where I grew up and where I live, so that was my home.

In Alexandria, I lived with my aunt and uncle in an apartment building filled with relatives from top to bottom. Every Friday, our whole family would have dinner at the grandparents’ apartment.

When not in class, students typically spend their free time with their families, forming a strong support system in the process — whether it be between older or younger relatives.

The kitchen was my and Aunty Nabila’s nightly hang-out spot. As we sat on the round wooden stools, eating sliced cucumbers and tomatoes, I’d read aloud the day’s reading assignment. They were long and challenging, and I scribbled new words and expressions in my notebook as Aunty Nabila explained them.

At the end of a particularly long day, she returned from work at around 10 p.m. Her eyes struggled to stay open, and I half expected her to fall asleep right on the couch. Instead, she plopped onto a stool in the kitchen and called,

“Where’s the article for today?”

I mentioned just once that I really loved peaches. The next day, my uncle brought home a big bag of the best peaches I’ve ever tasted.

It was wonderful inside our apartment building sanctuary. But outside its walls, I picked up on glaring problems. Piles of garbage lined the streets. Men leered and catcalled at women without an ounce of shame.

Corruption seeped through every corner of the system.

Once, my teacher and I wanted to take a side street shortcut to walk to the bookstore behind the Alexandria Library. The officer standing guard looked us in the eye, tilted his head and said, “It’s against the rules…”

My teacher responded, “Thank you,” striding straight ahead as the officer looked the other way. My jaw fell in confusion.

“You just have to read the body language, Mariam,” my teacher said, shrugging her shoulders.

Every Egyptian was frustrated about this kind of misconduct. The taxi drivers, the street artists and the elders drinking tea would all tell you so.

But why did I care? I wasn’t Egyptian … was I?

I was Mariam Shalaby of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. Pittsburgh, which had clean air, orderly traffic and law and order. I appreciated law and order, which Alexandria lacked.

But at the same time, I loved Alexandria. While my name and half my blood were undeniably Egyptian, I felt like I had one foot in and one foot out.

I started to realize that another part of what makes a place home is the feeling of belonging. When one feels like they are a part of the fabric of the place rather than an outsider looking in, they belong.

I couldn’t deny that I was American. I looked at things with an American perspective. Some Egyptians would tell me their government provided stability. I saw the lack of democracy as stifling. An aunt, a physician, once told me she regretted focusing so much on her career.

“A woman’s life is her husband and kids,” she said. I felt like flipping a table.

Despite the occasional cultural disconnect, I usually felt like Egypt was my home. It was where I had come from, and here I was, back. I’d see “freedom,” “remember God,” and other messages and art in graffiti on the streets and think, “I adore the energy of this country.” Sometimes I agreed with Egyptian values, like unconditional respect for elders, that back in America had made me the odd one. People talked with their hands here, like I did. For once, I wasn’t the only person wearing long pants in summer for the sake of modesty. While Arabic sometimes confused me, there were times when I couldn’t get over its beauty and precision. I felt like it was a language meant to be mine by birthright.

Only a week before I left Alexandria, another person asked me, “Where are you from?” I found myself saying “I’m Egyptian by origin, but I live in America.”

I’d come to realize that a home wasn’t only where a person lives, or where one grows up. To belong to a home is also to love the place and want to return to it, despite its flaws. To love the people within it, and also feel like you are one of them. To feel like you owe something to the place, for what it’s given you.

As hugged my relatives goodbye and turned towards the airport, I felt a familiar sense of loss. I left behind the culture I had grown attached to, my family, my close friends and my other mother language. And again, the concept of home seemed so simple — it was a place of love, culture, belonging.

It’s who I am and where I’m from.

Write Mariam at mas561@pitt.edu.