It’s a Monday afternoon, and I hustle home after my Democratic theory class. A few minutes past 7 p.m., I call his phone number and ask to speak with Mr. Chokal-Ingam, the man who changed his racial identity in order to go to medical school.

A friendly voice answers me back, telling me to call him Vijay and assuring me it’s fine to ask him whatever I please. We immediately dive into the details of his scam.

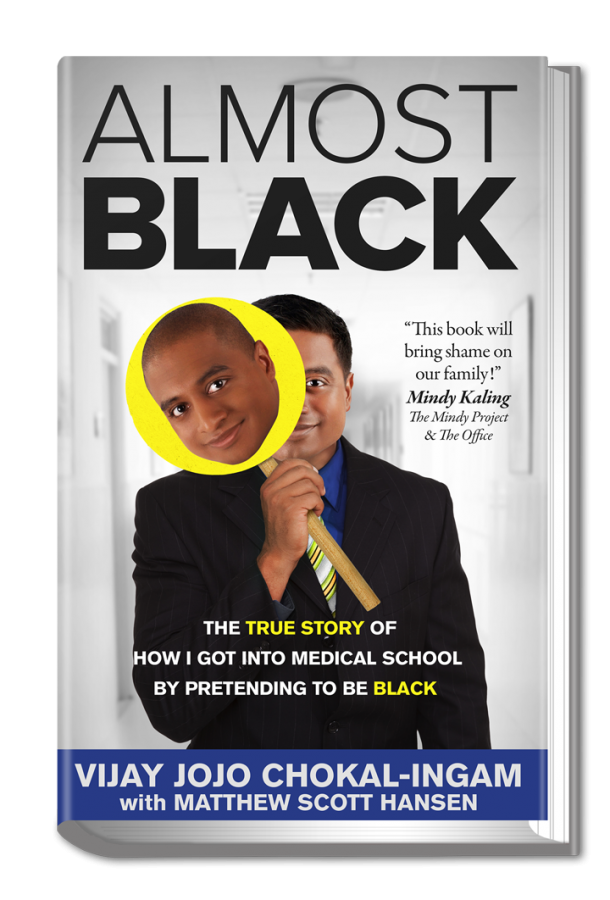

Chokal-Ingam is the author of “Almost Black: The True Story of How I Got into Medical School by Pretending to be Black.” His book chronicles his “misadventures” as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago applying for medical schools around the country. But there’s a twist. He didn’t apply as Vijay Chokal-Ingam, but rather as Jojo Chokal-Ingam, his identical counterpart in all ways but one: Jojo is black.

What originally started as a “scam” to get into medical school despite his poor grades and test scores has inspired Chokal-Ingam to come out as a staunch opposer of affirmative action. Despite interviewing and applying in 1998 and 1999, Chokal-Ingam is now using his experiences to support Donald Trump for president, citing Trump’s promise to appoint conservative justices to the Supreme Court who will oppose affirmative action legislation.

Nowadays Chokal-Ingam is an admissions consultant for the SOS Career Services in Los Angeles. After dropping out of Saint Louis University School of Medicine, he went on to get his master’s from UCLA.

Using statistical data from the American Association of Medical Colleges, Chokal-Ingam believed his chances of getting accepted into medical school in the ’90s would significantly increase if he applied as a black student. By changing his name, cutting off all his hair and trimming his eyelashes, he carried out this experiment by applying to 22 prestigious schools as a black student — including Pitt’s School of Medicine, where he was eventually rejected.

Flash forward to 2016, and his experiences lead him to self-publish a book. In the process of promoting the book, his media contact reached out to The Pitt News, which is how he got to me.

We spoke about his grievances with affirmative action and his experiences with racism. For him, these two concepts are one in the same.

“Racism is racism, whether you call it affirmative action or apartheid or whatever,” Chokal-Ingam said, a sentiment he repeated throughout our talk.

It’s perhaps the heartbeat of his argument and that of many opponents of affirmative action: that because affirmative action takes race into account and gives racial preference, it is racism. But I disagree. It’s just not that simple.

The crux of how racism works in America has to do with assumed hierarchy, meaning that when we look at race in our country we have to take into account the centuries of oppression levied by perceived dominant groups, usually white people, against black Americans, Hispanics, women and other disenfranchised groups.

John F. Kennedy first instituted the policy in 1961 via Executive Order. Kennedy’s goal was to highlight the government’s commitment to ensuring equal opportunity for all in the face of the intense and apparent racism of the American ’60s.

Students of color are still suffering from the effects of the ’60s. Persistent institutional racism means we still need affirmative action policies.

Chokal-Ingam doesn’t deny the intensity of racial problems today, citing his own experiences of discrimination when he was pretending to be black. He told me about being accused of shoplifting at a local grocery shore near the University of Chicago and about being pulled over on Lake Shore Drive — all things that had never happened to him when he was Vijay.

Still, he argues against giving minorities an advantage in college admissions. Recognizing the deeply ingrained problem of racism in our country while at the same time proposing to take away policies that counteract the weight of that racial disadvantage seems counterintuitive.

Chokal-Ingam, and other affirmative action opponents, favor a solely socioeconomic approach to affirmative action, one that doesn’t take race into account at all, meaning the policies take more initiative in ensuring students from low-income backgrounds receive a leg-up in college admissions.

That’s fair. The income-based achievement gap is a real issue, and I don’t disagree with the idea of making sure we have economic diversity in our higher institutions of learning in addition to race, ethnic and gender diversity. But where the logic fails is in connecting the way systemic and everyday experiences of racism and prejudice set back minorities when it comes to educational opportunities.

Income- and race-based affirmative action approaches aren’t always mutually exclusive. Race inherently affects socioeconomic status — studies have shown that public schools predominantly attended by students of color are woefully underfunded. Early education is one of the most crucial factors in upward mobility. Making socioeconomically-based affirmative action the be-all-end-all of affirmative action legislation would be akin to saying that minority groups who benefit from classic affirmative action policies no longer suffer from the institutionalized discrimination that inhibits equality of opportunity.

The American Community Survey did a five-year study from 2009 to 2013 on poverty among races in cities around the United States. In St. Louis, more than 29 percent of black Americans live in poverty while only 1.6 percent of white people do. Likewise, in Chicago it’s 35 percent black to 4 percent white. Black Americans are already more likely to live in poverty and when they do, it’s concentrated poverty where these economic disadvantages spread to the infrastructure, the businesses, the parks and — perhaps most importantly in this case — the schools.

Affirmative action based only on socioeconomic status doesn’t take into account the prejudice minorities, even wealthy minorities, encounter every day. A poor black child is still going to experience more discrimination because of his or her race than a poor white child, because that’s how systemic racism works.

Even if we base affirmative action solely on income, a black family is still more likely to be disadvantaged by a low income than a white family.

In addition to creating equal opportunity and attempting to reverse the effects of years of discrimination, affirmative action also helps to create diverse populations of students in higher education institutions. In states that banned affirmative action, numbers on diversity and minority enrollment dropped in nearly all cases despite the state’s overall populations of college-aged minority students growing.

California banned affirmative action in 1998. A 2015 New York Times study tracked the data on black and Hispanic enrollment before and after the ban. The average Hispanic enrollment at University of California, Berkeley was 18 percent from the year 1990 up until the ban in 1998. The average after the ban, as recorded from 1998 to 2011, is now 14 percent. This demonstrates that even though the number of Hispanic students who were old enough to attend college increased, less of them enrolled after the ban.

And there have been similar trends in Texas, Michigan and Washington state: when you ban affirmative action, minority enrollment drops even when the overall population of these minorities in the state is growing. This past summer, the Supreme Court made the decision clear in Fisher v. University of Texas that affirmative action is constitutional, and schools have the right to continue using race-based admissions programs.

Achieving this diversity in higher education institutions is a vital step toward a society where race-based affirmative action isn’t a necessity. An open dialogue about societal issues is better when a diverse array of voices are involved in the conversation.

This isn’t a problem with affirmative action or with people from marginalized groups, it’s a problem with broader society. When we fail to even try to understand affirmative action on its own terms and instead use it as a weapon to levy out more social discrimination against minorities, then we’ll never get to a place where we don’t need affirmative action policies.

In the end, Jojo didn’t benefit that much from affirmative action. Of the 11 medical schools he received interviews to, he got waitlisted at four and accepted only to one, the Saint Louis University School of Medicine. In addition to the fact that Jojo only applied as the black version of himself, we’ll never know for sure the discrepancies in admission that Vijay and Jojo may have actually faced. But it doesn’t really matter.

Just because Jojo is black doesn’t mean we should hand him his pick of acceptances to medical schools without question, but it does mean he would have experienced a lifetime of racism and prejudice that Vijay simply wouldn’t have, regardless of either’s socioeconomic status. What affirmative action aims to do is provide a counterbalance to the discrimination Jojo would have faced throughout his life and put him on even footing with Vijay to get into medical school.

Racism, discrimination, creating equal opportunity. You can call affirmative action whatever you want. But until we understand why we need the policy in the first place, it deserves to stay.

Amber primarily writes about gender and politics for The Pitt News.

Write to her at aem98@pitt.edu.