When Nyle DiMarco was 24-years-old, a friend asked him if he ever wished he could hear.

He immediately replied no.

“I told him, ‘I have always been deaf. It is part of who I am,’” DiMarco said. “Why would I want to be any different?”

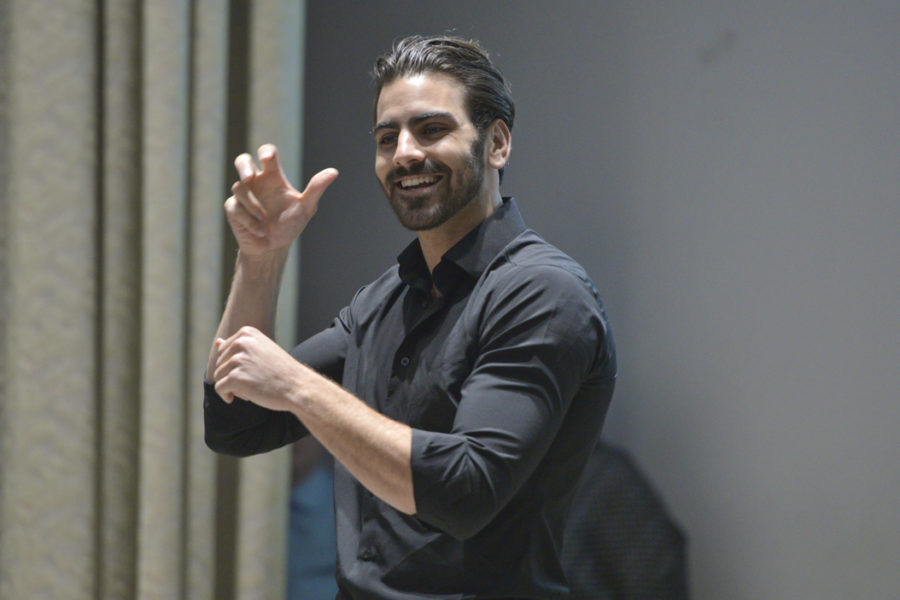

This is the message the actor and model relayed to nearly 200 Pitt students, faculty and community members of Pittsburgh’s Deaf community at the Frick Fine Arts auditorium Monday night. DiMarco was the first Deaf contestant on “America’s Next Top Model,” the second on “Dancing with the Stars” and the first Deaf winner of both. Pitt’s Rainbow Alliance invited him to speak about his work and life experiences.

“We figured that inviting him would be a great way to bring people from different backgrounds together and be a learning experience for those outside the communities he belongs to,” said Rainbow Alliance President Peter Crouch.

The event was free to all attendees, with reserved seating in the front four rows for Deaf individuals. Representatives of Pitt’s American Sign Language club were present to serve as interpreters.

When DiMarco walked onstage, hearing fans applauded, while members of the Deaf community held their hands in the air and shook them.

“Glad to be here in Antonio Brown’s hometown,” he signed, referencing his “Dancing with the Stars” opponent. His translator, Ramon Norrod, spoke what he signed for the non-ASL speakers in the room.

During his presentation, DiMarco spoke about his experience growing up in an entirely Deaf family and some of the trials he faced as a hard of hearing individual in hearing schools. He described the first Deaf school he attended in his birthplace of Queens, New York, as unchallenging and unfit to teach deaf students.

“I could sign better than anyone in my class, as well as most of my teachers,” DiMarco said.

Unsatisfied with the Deaf schools in their area, his family moved to Texas so that DiMarco and his siblings could attend a better school, one run by members of the Deaf community. There, DiMarco said he realized the ASL community was where he could truly thrive.

“Being there, it gave me a sense of self-confidence and pride,” he said. “I learned that being deaf is not a disadvantage. It’s an asset, a strength we should all embrace.”

DiMarco also recounted his time at Gallaudet University, the only college specifically for Deaf individuals in the world — “Deaf people’s Mecca.” He also told the audience about how he was contacted by “America’s Next Top Model” on Instagram and his experiences on the show. In various instances on the show, DiMarco sat alone while the other contestants gossiped or discussed their own drama — he often talked about being isolated by their disinterest in including him.

“To be human is to have language, and I was pretty much without language for the two months on that show,” he said. “People would say they’d want to learn more from me [about Deaf culture and ASL], but never bothered. It was pretty isolating.”

DiMarco said he stuck with the show because he knew he was making an impact and inspiring other Deaf individuals. After he won the top model slot, “Dancing with the Stars” reached out to him. His partner, Peta Murgatroyd, was initially unsure about dancing with him, but they made it work.

“She’d tap me for when to start and scratched my back as a way to say ‘go faster,’” he said.

DiMarco said he was glad he was able to represent the Deaf community on “Dancing with the Stars” to tell a story, incorporating parts in his dances where he and his partner danced without music to show to the world what he experienced during practice.

“People were crying during those parts,” he said. “They got to understand how my life worked.”

DiMarco also spoke about his organization, the Nyle DiMarco Foundation, a non-profit for Deaf children and their families.

“We’re working with legislators right now to pass more bills providing resources and making the world more accessible for Deaf individuals,” he said. “Whenever I do this work, I always keep in the back of my mind that our differences are our strengths.”

At the end of his presentation, DiMarco taught the hearing individuals in his audience how to say “embrace yourselves” in ASL — hands in fists, crossed over the chest and then a thumbs up.

After he finished, Lindsay Surmacz, a program coordinator at Pitt’s Institute for Clinical Research and a hearing individual, asked DiMarco what educators needed to do to make the classroom more accessible and inclusive.

“Include aspects of their history and culture, definitely,” he said. “Plus, it helps if you know ASL.”

Surmacz said she was glad she attended DiMarco’s talk because she feels not enough conversation occurs between Deaf and hearing individuals, which negatively impacts both groups.

“People need to be able to understand each other to help each other and be inclusive,” she said.

Hannah Adams, a sophomore communication science and disorders major, attended the talk to see a prominent member of the Deaf community that she’d been a fan of since he rose to fame. Adams, a hearing individual pursuing an ASL certificate, said she thinks it’s cool that someone in the media is raising awareness about Deaf issues.

“A lot of hearing people don’t know much about Deaf culture,” she said. “Now they have the chance to gain a perspective, to learn.”