Review | “Lost Girls” demands to be seen

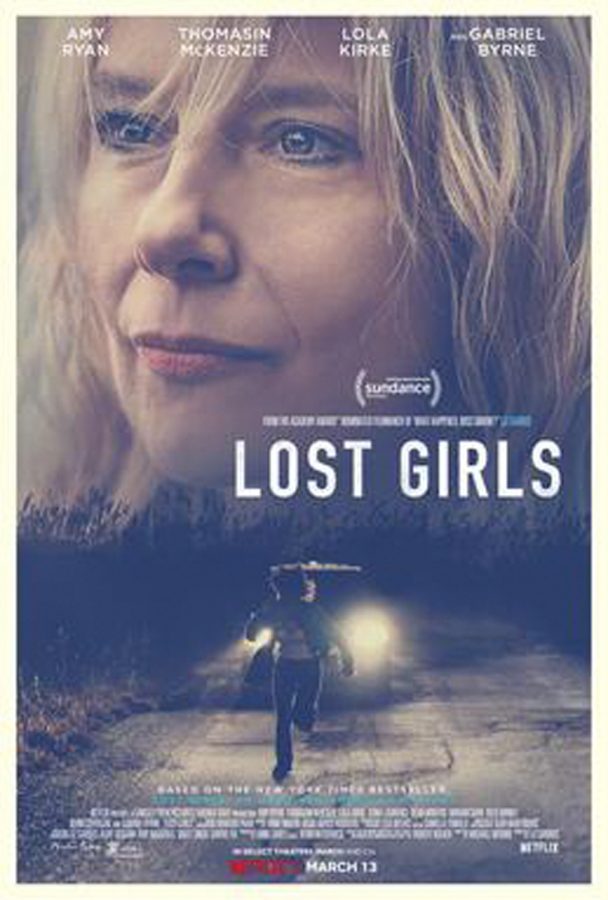

“Lost Girls” release poster.

March 17, 2020

Growing calls to decriminalize sex work in recent years have brought attention to the dangers faced by those in the profession. Now streaming on Netflix, the new film “Lost Girls” from director Liz Garbus asks us to reconsider our preconceived ideas of these women and their work.

The movie is based on the true story of Mari Gilbert, an overworked, disgruntled mother portrayed by Amy Ryan. Gilbert’s daughter Shannan, a sex worker, went missing in 2010 after meeting a client in the private Long Island community of Oak Beach.

The film begins when Shannan fails to show up to family dinner. Unable to contact her daughter, Gilbert files a missing person report, only for the police to initially ignore it. Gilbert realizes that she must take matters into her own hands, and sets off to Oak Beach with her two younger daughters, Sherre and Sarra, to find out for herself what happened.

While searching for Shannan, the Oak Beach police uncover the bodies of four other murdered sex workers. Gilbert finds her life suddenly intertwined with those of the women’s mothers and sisters, all of whom have become disillusioned by the law enforcement’s unwillingness to help.

The plot of the film reveals deep issues with the way in which law enforcement and the media treat sex workers. They are seen as having put themselves in danger — their murders are chalked up to the risks of the job and their cases aren’t taken seriously. The film challenges these harmful stereotypes every step of the way — these girls had families who loved them, and their deaths were tragedies rather than somehow their own fault.

One of the victim’s sisters, Kim, played by Lola Kirke, is a sex worker herself who soon finds a place among the other mourning women. Here, the film best offers a view into the nuanced lives of sex workers. Kim is happy despite having lost a sister and smart despite the stigma against her. She’s unapologetic in her behavior but never standoffish.

Most importantly, when the other women question her profession, they do so out of fear for her safety rather than from a place of judgement. The special relationship between Kim and the victims’ families speaks to the power of unconditional female solidarity in which women refuse to condemn each other.

“Lost Girls” is undoubtedly a feminist film and comes at a time when feminism is at an impasse between belief in women’s sexual empowerment and fear of patriarchal control and violence. The film does something radical, then, by portraying sex workers not as traumatized, helpless girls or objects for male pleasure, but as human beings. “Lost Girls” manages to criticize the circumstances surrounding their deaths while refusing to portray their work as immoral.

While Gilbert searches for her daughter, the community of Oak Beach grapples with the ugly events that unraveled in their backyard. The residents see Gilbert’s investigation as little more than an annoying disturbance of the peace, but this supposed beachside paradise seems to hide a dark secret, as demonstrated by the neighborhood’s sinister aesthetic.

What should be a scenic ocean view is an overgrown, bushy marsh. Instead of pastel beach houses, the landscape is full of homes with dark wood siding, dirty sliding-glass doors and creaking staircases. With the sky constantly gray and the sea breeze whipping characters’ hair, the viewer feels the anticipation and danger of an approaching storm and is never fooled by the claim that Oak Beach has nothing to hide.

The real highlight of the movie, however, is Amy Ryan’s performance. Gilbert herself is a whirlwind, oftentimes putting her own safety on the line in search of her daughter and constantly confronting the police about developments in Shannan’s case.

She devotes herself completely to the search, and Ryan portrays her grief in a nuanced way. Gilbert is frequently confrontational — sometimes in a productive manner that leads others to act quickly, other times in a destructive manner that pushes her loved ones further away. Through all of the anger, the viewer can still sympathize with Gilbert. Ryan clearly understands the meaning of the term “tough love” and her character’s overpowering desire to make things right.

Ryan also shines during those moments in which Gilbert most clearly doesn’t have control. Viewers are reminded that she is just a mother, and Ryan makes her fear and confusion almost palpable. Here the real driving tension behind the film also comes through — Gilbert both needs and wants to take matters into her own hands, but she must confront the fact that she can’t solve the case by herself.

The choice between who to believe and who to be suspicious of is never set in stone, and at times Gilbert must rely on Commissioner Richard Dormer (Gabriel Byrne) to make those difficult decisions. With new leads constantly rising to the surface, the plot seems to run in circles, making it feel stagnant at times. Still, while frustrating, this constant cycle puts the viewer in Gilbert’s shoes — slowly losing hope with every lead that turns out to be a dead-end.

The film may be difficult to watch, full of fear, frustration, heartbreak and hopelessness, but it’s worth the emotional effort. “Lost Girls” is a testament to the power of women’s voices, and these women certainly have something important to say.