‘Men in Place’ charts a changing landscape of masculinity

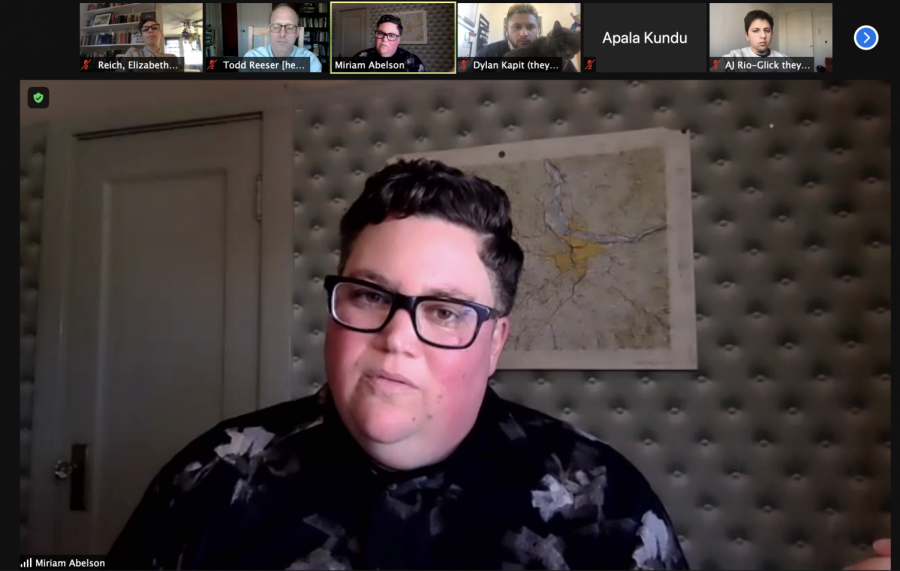

Miriam Abelson, a sociologist and associate professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Portland State University, spent nine years interviewing 66 transgender men across the country.

March 5, 2021

Miriam Abelson, a sociologist and associate professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Portland State University, spent nine years interviewing 66 transgender men across the country. The result of her work, the 2019 book “Men in Place: Trans Masculinity, Race, and Sexuality in America,” explores the intersections of trans experience in America.

Abelson discussed “Men in Place” with a panel of Pitt professors and students on Wednesday. The Zoom event was open to the Pitt community, but accompanied the graduate seminar Masculinities in Theory and Practice, taught by Todd Reeser, chair of the French department with a secondary appointment in gender, sexuality and women’s studies.

The panel included AJ Rio-Glick, a first-year graduate student in the sociology department, David Tenorio, an assistant professor of Hispanic languages and literatures and Elizabeth Reich, an assistant professor of film studies.

“Men in Place” operates under the idea that people do not have a natural gender, but rather that gender is a social construct. Tenorio explained that masculinity, and gender itself, is the result of our culture rather than our biology.

“[The book is] really adding to critical masculinity studies, and how gender is not something that is given, but it’s something that is learned,” Tenorio said. “You’re primed to believe that gender is based on our biological differences, when in fact it is a practice defined by space, by interactions with others.”

Abelson argues that masculinity itself changes depending on what social contexts men occupy.

She also puts forward the idea of “Goldilocks masculinity” to describe the pressure trans men feel to behave masculinely enough to be seen as men, but not so masculinely as to seem threatening — a phenomenon she said she noticed repeatedly amongst the subjects of her study.

“It seemed almost like, at times, a sort of balancing act, in a way that I think most people experience, but I think this group of folks were able to articulate in particular ways,” Abelson said.

Race also factors into trans men’s ideas of masculinity. Abelson said for Black trans men and trans men of color, the feeling that others perceive them as men also comes with fear of persecution by law enforcement, as well as a self-consciousness around looking at white women in public.

“We can’t understand masculinity without understanding race at the same time,” Abelson said. “I’m thinking of some of the Black and Latinx men who I interviewed. Even if they were actually not looking, they’re still accused often of looking, or of being threatening in that space.”

Reeser described “Men in Place” as groundbreaking in its scope and approach, in that Abelson uses ethnography — a means of collecting information through participant observation and in-depth interviews — to compile a detailed survey of trans masculinity in the United States.

“It’s really a definitive study of American masculinity from an international perspective that is based in ethnography,” Reeser said. “[Abelson’s] work is about interviewing — collecting interviews to think about broader gendered phenomena in the U.S. in the 21st century.”

Abelson’s study began in 2009, with a series of interviews with trans men in the San Francisco area. She said she broadened her scope to encompass rural areas, especially in the South and Midwest, after hearing some of her subjects express that they felt fortunate living in large, progressive, coastal cities.

“Being a sort of stubborn and contrary person, I said, ‘Well, if I’m going to continue this project that’s where I need to go. I know that there are trans masculine people in the South,’” Abelson said.

Rio-Glick, who is originally from upstate New York, said they thought Abelson’s inclusion of subjects outside major urban centers provides a perspective often absent from conversations about trans identity.

“I think especially in the queer public consciousness, there’s a lot of people in these sort of areas in these big cities, and we don’t really know what is the Midwestern or rural experience of trans people in general. And so for her to go and collect this, I think it’s pretty groundbreaking,” Rio-Glick said.

In addition to being from both urban and rural areas, Abelson’s subjects also identified both as men and as nonbinary, although she said part of her criteria for choosing interviewees was that they were all “social men.”

“Some of the people identified as nonbinary or genderqueer,” Abelson said, “but they had a relationship to that sort of social category of man and were OK being called that, too.”

The boundaries between trans masculine and nonbinary gender identities often blur together, and many individuals position themselves as both. Trans men have also historically occupied lesbian spaces, while others “go stealth” — meaning they stop disclosing their transness or stop identifying as trans altogther — after they transition. According to Reich, the current narrative around what transness is and isn’t doesn’t accurately reflect the experiences of those individuals.

“Some of them lived full time as men,” Reich said, “and really found it very important to be in lesbian spaces and able to use she/her pronouns there, because they actually felt so hemmed in by what felt like an enforced masculinity or just a terminology and stability around masculinity that they wouldn’t have chosen.”

Rio-Glick, themself nonbinary and trans masculine, expressed discomfort with the assumption some of the men in the book made, that transitioning holds absolute maleness as its goal.

“In my constructions of masculinity, and a lot of my friends’, there’s this discussion of, what does it mean to be transitioning towards masculinity when you do very much feel the weight of your womanhood?” Rio-Glick said. “One of the things that I have been explaining my own identity is asking people to hold the nuance of seeing me as both male and female.”

Abelson said she still grapples with the instability of the border between butch and trans identities, and that seeing her friends grapple with those same issues surrounding feminism and masculinity spurred her research 12 years ago.

“The things that were happening around me was [that] my friends were transitioning, and there were people that would have called themselves butch at the time, and maybe still would… were grappling with this idea and I was grappling with these ideas of masculinity,” Abelson said.