Uncertainty defines first month of new NIL rules

Kaycee Orwig | Senior Staff Photographer

Universities, conferences and the NCAA have reaped major financial benefits from the efforts of college athletes. Their “amateur” status prevented them from being paid for more than 100 years — but times are changing.

August 17, 2021

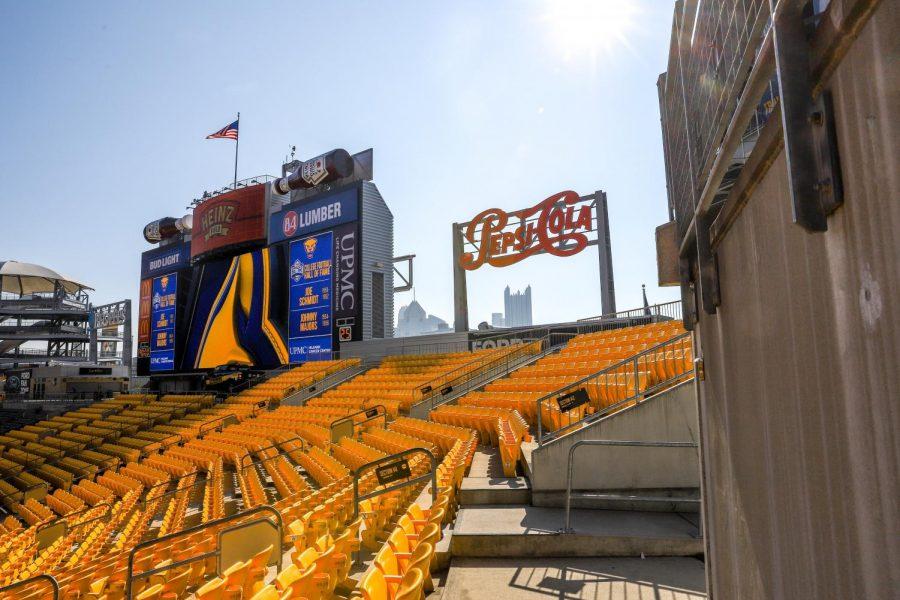

The Pitt band, cheerleaders and dance team paraded through the North Shore towards Heinz Field. Pitt flags waved, with blue and gold jerseys dotting the streets as the City skyline watched over the scene. Pittsburgh was alive with energy.

Trumpets blared, drums pounded and fans cheered as the Panthers commenced their trek out of the locker room, through the tunnel and onto the field before a game against the North Carolina Tarheels in November 2019. Heinz Field erupted and tens of thousands of Panther fans seemingly fell into a college football induced trance.

But as the saying goes, ignorance is bliss.

Pitt football head coach Pat Narduzzi’s salary was $4.73 million during fiscal year 2020, which ran from July 2019 through June 2020. The Pitt football program brought in more than $37.8 million that same year, as the Atlantic Coast Conference accrued $497 million. And the mastermind behind it all, the NCAA, raked in more than $500 million that fiscal year — even with college sports being put on hold in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The same Pitt Panthers who were wearing the shoulder pads and storming out of the tunnel didn’t see a single penny.

Since its inception, the NCAA has held that college athletes cannot and will not be paid for their name, image or likeness. Athletes were ineligible to accept endorsements or receive payment for their performance — all to maintain the amateurism surrounding college athletics. NCAA President Mark Emmert went as far to call a shift to allowing players to capitalize on their NIL an “existential threat” to college athletics.

But new rules and regulations regarding name, image and likeness benefits for college athletes will change this long-standing rule.

Until recently, there was a $5,000 limit on educational benefits outside of tuition and board that schools were allowed to provide to their athletes. But a Supreme Court ruling in June removed the cap. In the concurring opinion that Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote, he put the NCAA’s entire business model on blast and it seemed the castle the NCAA built up was finally crumbling.

“The NCAA’s business model would be flatly illegal in almost any other industry in America,” Kavanaugh said.

But many of college athletics’ leaders staunchly defended this system for decades, claiming the change would take the spirit out of college athletics. Pitt Athletic Director Heather Lyke expressed some hesitation in May regarding the potential shift to collegiate athletes being eligible to capitalize off of their name, image and likeness.

“[Pitt Athletics is] supportive of this type of legislation,” Lyke said. “I think the biggest challenge again is [NIL] focuses on your name, your image and your likeness … it’s kind of counterintuitive to what the team is about … that’s the only thing, that name, image and likeness sends a message to young people that ‘there’s a value that’s placed on me.’ I don’t love that philosophy or mentality that comes out of name, image and likeness. But we’ll manage through it.”

Just over a year ago, Lyke said in an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that students signing and selling merchandise “didn’t feel quite right.”

The June ruling seemed to be the first of many dominoes to fall in the coming weeks as many states, including Pennsylvania, passed legislation allowing college athletes to capitalize off of their NIL — forcing the NCAA to pass NIL rules of their own.

Now the NCAA and leaders such as Lyke have shifted their tone toward more of a cautious excitement for athletes.

“Our goal is to be progressive, innovative and helpful in every aspect of their student-athlete experience, and the world of name, image and likeness is no different,” Lyke said in a June statement. “We look forward to helping our student-athletes learn more about this topic.”

Shortly after the new laws passed, athletes took to social media to express their excitement and open their inboxes to anybody who wanted to form a partnership.

Fifth-year quarterback Kenny Pickett made waves through not just the Pitt community, but the entire college sports landscape when he announced his first endorsement deal. It was different in the sense that he wasn’t being paid cash. Instead, he would promote the Oaklander Hotel’s Spirits and Tales restaurant one time on social media in exchange for a weekly dinner for his offensive line.

Pickett has since released his own logo and a partnership with a local radio station, as well as an agreement with a trucking company to benefit the Boys and Girls Clubs of Western Pennsylvania.

While Pickett is inherently in the limelight due to his prominent position with Pitt football, other athletes’ endorsements haven’t been given nearly as much attention.

The Pitt News reached out to the athletics department for statistics regarding NIL deals within its programs, but spokesperson R.J. Sepich declined to provide any information, deferring to athletes to announce deals themselves.

Although these rules are not meant to be used to recruit high school athletes, there is some concern that the policing of rules meant to prevent NIL being used as a recruiting piece will be loose and open the door for bigger schools to monopolize the recruiting pools. Even Lyke herself admitted it could be used as a means of recruiting in a July press conference.

“We can’t recruit student athletes with the idea of ‘Hey, come to Pitt because we can set you up with these name, image and likeness opportunities,’” Lyke said.

But Lyke quickly qualified her original statement.

“There’s an indirect recruiting piece to it,” Lyke said. “Certainly schools are going to promote the fact that ‘We have X number of followers’ or ‘We can grow your followers with an outside company ’ … There’s no question there will be that type of indirect recruiting spiel.”

Narduzzi, too, expressed some concern about the direction college football was heading with the new NIL laws.

“What’s going to happen of college football?” Narduzzi said in an interview on 93.7 The Fan in early August. “There’s pretty much legalized cheating out there now going on with this name, image and likeness. I think it’s great for our kids, but I wonder where it takes college football.”

The No. 1 football prospect in the 2022 class, quarterback Quinn Ewers, decided to skip his senior year of high school and enroll at Ohio State sooner than most anticipated. Ewers was told he could not capitalize off of his NIL in high school — but as an Ohio State Buckeye, he would have the corporate world at his fingertips, with endorsement deals already reportedly lined up.

Head men’s basketball coach Jeff Capel spoke for many regarding the NIL rules — nobody really knows what to expect.

“Anyone that said that they understood what was going to happen on July 1 — they’re lying to you,” Capel said. “I don’t talk about things I’m not educated on.”

NIL rules and endorsements — a situation that has been likened to “the wild, Wild West” — are still in their infancy and it remains to be seen how it will impact college athletics long term. But one thing is certain — college athletics will never be the same.