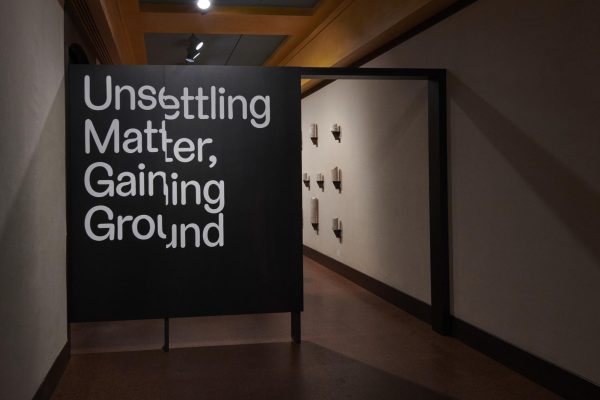

At the Carnegie Museum of Art, a haunting, melancholic melody replaces the usual tranquil notes of classical music. The art exhibit “Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground” transforms the gallery into a space that dares to confront, challenge and provoke as it delves into the urgent realities of the industrial world.

From Aug. 19, 2023 until Jan. 7, 2024, the Carnegie Museum of Art presents the exhibit, which uses art to tell intricate stories of how fossil fuel economies have been created and sustained. Through various media, including paintings, sculptures and films, the art delves into the historical and contemporary aspects of extraction processes and their societal consequences.

Three of the exhibit’s pieces come from the permanent collection of the museum, including a series of mining infrastructure designs and architectural drawings. The remaining seven pieces came from artists who focused on the history of fossil fuels and the climate crisis. These include a solid fossil fuel core sample, a photo of an oil pipeline in the Allegheny National Forest, paintings depicting mining machinery and other artworks.

Associate curator Theodossis Issaias and curatorial research fellow Ala Tannir of the Heinz Architectural Center co-organized the exhibit. Issaias said the exhibit is the result of years of work reflecting on society’s extraction of natural resources from the earth.

“We started working on this project more than two years ago, and our intention was to reflect on the region that we inhabit,” Issaias said. “There is an unbelievably problematic and contentious history of extraction, and we understand extraction as one of the quintessential processes of modernity, this type of colonial extractive relationship with the land.”

Julia Huczko, a senior ecology and evolution major, said she chose to visit the exhibit because it strongly resonates with her passions. Huczko said despite constantly learning about climate change and the repercussions of industrialization, seeing it felt more powerful.

“I study ecology, and my entire degree revolves around the ramifications of the climate crisis and its origins, making this exhibit an ideal fit for me,” Huczko expressed. “No matter how many professors articulate the concepts of pollution and environmental damage, nothing compels you to confront the unvarnished reality of our existence quite like witnessing a painting depicting a monstrous mining machine devouring nature.”

Tess Marchesin, a gallery associate at the Carnegie Museum of Art, shared their observations of visitors’ reactions to the art in the exhibit. Marchesin said they find joy in seeing people learn about the history of extraction through art.

“Getting to see people’s reaction to [the] exhibit, I really enjoyed it,” Marchesin said. “Everything in here is focused on the rights of people and nature, and seeing the light bulbs go off and that moment of discovery as visitors connect with each piece is really touching.”

Issaias said the process of understanding industrialization and the climate crisis includes studying the history of extraction. Issaias said there is a connection between the early industrialization hundreds of years ago and today’s methods of extraction.

“In order to be able to understand both the system and how the system plays out today in the current climate breakdown and environmental degradation, we have to break things down,” Issaias said. “Let’s go to the origin, to the very beginning of coal mining in Pennsylvania and today’s fracking and try to connect those.”

Marchesin said the breadth of information in the exhibit may leave many visitors feeling overwhelmed. Marchesin said they believe it’s important for visitors to keep an open mind.

“We have multiple video installations and there are multiple audios playing, every wall has something going,” Marchesin said. “For a first-time visitor, it can be very overwhelming, but the most important part is to open yourself and maybe be okay with reading with some chunks of text.”

Issaias acknowledged that it was important to be self-aware during the exhibit’s conception. Issaias said the Carnegie Museum’s namesake was a fundamental element of the exhibit’s statement.

“First and foremost, the museum is called Carnegie Museum of Art. [Andrew] Carnegie was a great philanthropist and industrialist, but we also say he was a robber baron,” Issaias said. “The very fact that the museum exists is a testament to the extractive processes, and it also shows how philanthropic capital comes in and supports art and public institutions, so it’s important for us to be self-reflective and show those things.”

Marchesin said they were most intrigued by “The Continuous Miner,” an art piece that portrays industrial machines from a new perspective, much like Huczko. Marchesin said the original idea behind the painting was to promote mining machinery, but instead, it showed a horrific side of industrialization.

“My favorite part of the exhibit is the ‘Continuous Miner’ portraits. It’s a really cool project where the painters were commissioned by the Pittsburgh Fortune Magazine to highlight the machine,” Marchesin said. “The artists subverted those intentions and almost portrayed the machine as a monster, and to me that’s a metaphor for what Pittsburgh has gone through with industrialization.”

Issaias said one of the most important takeaways from the exhibit is the myriad of histories associated with Pittsburgh. Issaias said the exhibit seeks to offer contemporary perspectives on the environmental crisis, intertwined with the enduring narratives of resilience.

“There are many histories of Pittsburgh, as countless as the butterflies that have graced the city’s skies,” Issaias said. “We’re not trying to narrate a comprehensive history of Pittsburgh, we’re instead trying to find ways to represent this environmental crisis, but also the perseverance and activism that is all around.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to include the name of the co-organizer of the exhibit.