By the time Carey Wasa graduated Pitt in 2013, he had a stockpile of textbooks sitting on his windowsill that weren’t worth even trying to sell.

“It hit me that there are students who probably need these books for classes, and I have them right here,” Wasa said.

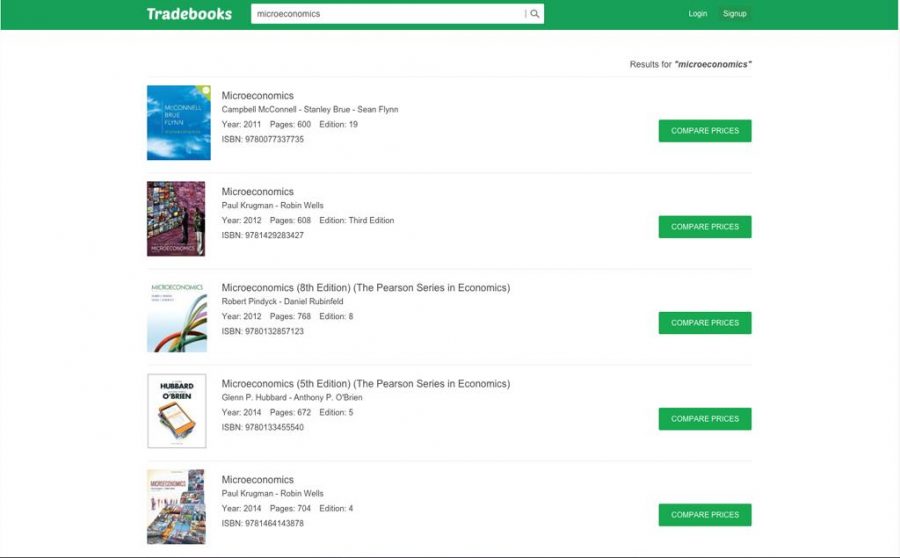

Wasa pitched the idea of starting a textbook exchange company to Olisa Okonkwo, a Carnegie Mellon University graduate, and Briand Djoko, a Pitt Ph.D. student, in 2014. Working from their own computers for seven months, the three men launched Tradebooks.co, a website that connects student sellers to student buyers on the same campus, in Sept. 2015.

Okonkwo, the CEO of the company, designed the site while Djoko, the chief technology officer, wrote the code. Wasa, the chief marketing officer, spread the word about the upcoming launch through a Facebook page.

According to a 2014 study from the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, 65 percent of students have chosen not to buy a required text because of its cost, even though 94 percent knew it may have a negative impact on their grade.

Since September, Tradebooks has allowed students to buy and sell books from each other at lower prices than traditional retailers.

When the site launched, it included a price comparison tool so users can compare textbook prices at Amazon, Chegg and Half.

When a student wants to sell a book on Tradebooks, the site uses its price comparison tool to suggest a competitive price range. The site first lists students selling the book on their campus for face-to-face exchanges. If there aren’t any books available on their campus, the site uses its price comparison tool to suggest other places to purchase the book.

When a user purchases a book through the price comparison tool, TradeBooks receives a five to 10 percent commission from the site selling the book. Although all team members are receiving a part of the commission, Okwonko said it is currently very small.

The site can’t yet charge students for using it to meet up and exchange books — bypassing the site’s payment system — and its founders currently put all the money they make back into the company.

After the initial launch, the company has focused most of its efforts on marketing, using friends and recommendations to reach 70 people, promote 200 books and bring in $3,000 worth of sales.

The site currently covers five campuses including Pitt, Duquesne, Carnegie Mellon, Drexel and Stanford. The founding members hope the site will grow to include several more campuses and give them each a full-time job.

“We’re really trying to help students. Most students have textbooks sitting at home, and every semester someone is taking the classes that require those books,” Wasa said.

Before they launched the site, the entrepreneurs competed and were finalists in the Randall Family Big Idea Competition, a competition the Innovation Institute holds annually. At the competition, experienced entrepreneurs and investor helped them finalize their business model.

Babs Carryer, director of the Innovation Institute, has seen successful startups come through Pitt’s programs, such as Nymbus, an app to increase audience participation in concert performances.

“Pitt is getting to be known as a place where students can be nurtured and developed into entrepreneurs and get support to turn their ideas into startups,” Carryer said. “I think students have the answers to potentially be able to solve a lot of the world’s worst problems.”

John Delaney, professor of business administration and former dean of the Katz Graduate School of Business, said students can always start websites and web-based businesses, but they have to put more into it to succeed.

“The idea needs to be good, but in many instances, it’s not just the idea,” Delaney said. “It’s the amount of time and effort to make it work, to market it, to get the money that you need to finance it appropriately and so forth, and that’s the piece that becomes the difficult one.”

When students come to Delaney’s office to pitch startup ideas, he asks them if they would be willing to drop out of school to pursue it. Though dropping out is not always necessary, Delaney said students need to believe in their idea to that extent to make it work.

“I think it’s rare that people can have success by chance,” Delaney said. “It’s more the hard work.”

In the future, the team hopes to partner with publishers, helping them to better market their books and allow the team to sell portions of a book to students in smaller booklets or individual chapters.

Marketing has been an issue for the team, which hired Jake Laskey, a Pitt sophomore majoring in communication and psychology, in December to help manage the advertising of its company.

High textbook prices are unlikely to go away in the near future, according to John Weidman, a professor of higher and international development education at Pitt. A textbook’s value decreases drastically after a publisher releases it because the book’s information can quickly become out of date.

“That’s why you don’t get much when you turn it in,” Weidman said. “The publisher is only collecting when they sell it for the first time. After that, the author makes the money.”

Although Weidman applauds the idea of less expensive books, he said it is not always feasible.

“I’m all for somebody organizing so that they can provide students with the opportunity to get materials at a reasonable price,” Weidman said. “The only thing you have to be careful of is if the editions change dramatically, then you’re much more limited in options.”

Wasa hopes the platform will serve as a way to save students money, as well as a social platform for college students.

“Students can connect on the platform with students in their classes and in their majors, and they can have contacts for when they have issues through the semester, like if they need help studying,” Wasa said. “We believe students can help each other.”