Pitt faculty prepare for union election, adjust campaigning amid pandemic

Faculty union organizers have had to turn to Zoom calls and emails to rally support.

February 17, 2021

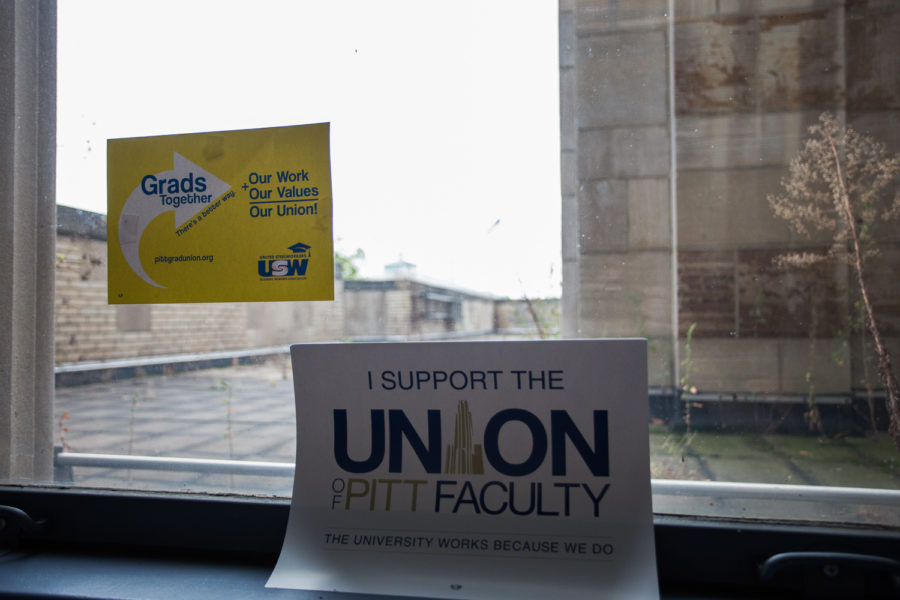

Melinda Ciccocioppo used to walk around campus proudly sporting her “Union of Pitt Faculty” button. She’s visited faculty offices, labs and classrooms for years to talk with professors about how a faculty union could improve their lives.

But since the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the psychology lecturer has had to rely on professors’ willingness to answer a phone call or email.

“I think overall it’s more difficult,” Ciccocioppo said. “Probably the biggest change is that we can no longer do class visits or office visits.”

Despite those hardships, faculty union organizing efforts have ramped up since March, when COVID-19 largely shut down Pitt’s campus and forced classes online. With a union election likely to take place in the summer or fall — according to representatives from United Steelworkers, the union assisting faculty and graduate students in their attempts to unionize — organizers have had to adjust quickly to make their message heard.

Instead of candid one-on-one conversations with professors after class, organizers have pivoted to Zoom happy hours and emails. Ciccocioppo said organizing in this way can make it harder to get new faculty on board.

“It’s hard to get a response sometimes to cold emails if people don’t know you,” Ciccocioppo said. “It’s easier if I’m reaching out to someone that I know, that works out better. But if it’s a faculty member that I’ve never met before, it can be hard to get a response.”

As the faculty union campaign reaches the five-year mark, Paul Johnson, an assistant professor of communications, said “enthusiasm for the effort remains very strong.”

Union organizers filed for an election in January 2019 after they said they collected signed authorization cards from the required 30% of Pitt faculty. The campaign up until that point lasted three years, but it was only the beginning of a long process.

The Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board ruled in April 2019 that organizers had not collected enough cards to trigger an election. Five months later, The Pitt News found that Pitt had included hundreds of administrators and retired professors on its list of union-eligible faculty. Labor Board hearing examiner Stephen Helmerich subsequently ruled that the Pitt-submitted list was “factually and legally inaccurate,” allowing faculty to move forward with an election. Due to the pandemic, the election will likely take place using mail-in ballots.

Pitt has also paid “union avoidance” law firm Ballard Spahr $2.1 million since 2016 to provide legal support during the separate faculty and graduate student union campaigns. Many organizers have slammed the payments as a waste of money.

Pitt spokespeople have repeatedly denied allegations that the University tried to stall unionization efforts.

“In every instance, Pitt has followed the process laid out by the PLRB,” Pitt spokesperson David Seldin said.

Organizers have had three main priorities since they officially kicked off their campaign in 2016 — improving pay, job security and transparency between the administration and faculty. For Johnson, an issue that’s become magnified during the pandemic is transparency. Pitt’s administration drew criticism from faculty over the summer after sending an “inadvertent” email to incoming first-year students about fall plans before informing faculty.

“People are frustrated when they find out decisions that are made about when students are coming back to campus, what the form of classes are going to take in the new semester,” Johnson said. “When they read about those in the news instead of receiving direct information from chairs and administrators.”

Many Pitt faculty also complained that they had little say in the implementation of Flex@Pitt, a part in-person and part remote learning model that Pitt instituted for the 2020-21 academic year. Ciccocioppo said the decisions surrounding this teaching model were a surprise to many instructors.

“One effect that the pandemic has had on organizing is that it’s really shed a light on how little say faculty have in terms of important decision making that happens, even involving our primary tasks, like instruction, for example,” Ciccocioppo said. “There was really no faculty input in terms of going to this Flex@Pitt model, it really kind of came out of the blue for all of us.”

Provost Ann Cudd said in May that the University’s fall-planning task force received “lots of input from students and faculty.” Chris Bonneau — president of the Faculty Assembly, which represents faculty on campus — served on the task force’s executive committee, and faculty were included in the working groups.

If the union election goes the way of organizers, the first step would be to elect faculty representatives from each department who could set up a committee to peer review employees’ contracts and address various grievances within the department. Tyler Bickford, an associate professor in the English department, said that process will be crucial for evaluating faculty needs.

“When we go into bargaining, we’re going to make sure we’re very closely communicating with the faculty about priorities,” Bickford said.

Organizers have long complained that adjuncts and visiting lecturers don’t have a voice in administrative decisions. They say improved representation could help mend the fractured relationship between top officials and lower-ranking professors.

Johnson said organizers “feel pretty confident” that a union bid will succeed. At least 50% of professors must vote yes to form a faculty union at Pitt, which would be affiliated with the Academic Workers Association, a division of United Steelworkers.

Organizers and Pitt have also argued about whether the School of Medicine’s faculty should be included in a faculty union. Pitt maintains that the medical school should be included, whereas organizers said when they petitioned for a union election that including the medical school would be unlawful because it had its own bargaining unit.

Now that Pitt has filed a motion to decertify the School of Medicine’s bargaining unit, organizers support incorporating medical school professors in the union. Medical school faculty were excluded from the union eligibility list Pitt submitted to the Labor Board, but up to 1,000 of them could be included in the bargaining unit when the Board orders an election.

The University administration has never explicitly come out against faculty unionization, but Cudd said in 2018 that she’s “not really clear on what the need would be” for a union. And Chancellor Patrick Gallagher said in the same year that “unions don’t always represent everyone equally well.”

Seldin did not say whether Pitt would try to challenge the timing of a faculty union election, but did say that “the University will address its suggestions for the timing of any faculty election with PLRB representatives if and when an election is ordered.”

While the pandemic has made campaigning more difficult, Bickford said it has also shined a spotlight on existing problems between faculty and administration.

“The pandemic also made it really clear that having a voice at work was really important, that these decisions really matter for our health and safety and economic security,” Bickford said. “For a lot of people, it really clarified why having a union would be a really good thing.”

This article has been updated to more accurately reflect union organizers’ stance on including faculty from the School of Medicine within a single bargaining unit.